Rio Grande weaving

Dan Fisher rug, 1939

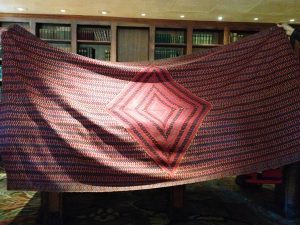

For cataloging training, Tawney and I brought the Dan Fisher rug, one of the Rio Grande weavings, down to the conference table from its location in a storage room. Wearing cotton gloves, we slowly unrolled the weaving onto a plastic sheet. As we examined the textile with care and detail, we filled out the Inventory / Object Information sheet, one of which is completed for every object in the museum collections.

After measuring and photographing the rug, we made a long visual inspection, noting dye colors, bands and stripes and the ticking pattern at the edges of most of the stripes. Alternating the weft colors along a single pass through the warp threads makes a ticking pattern, as seen in the below image.

Ticking pattern (gray into yellow-gold and gray into rust) and small area of damage in blue area

We studied the condition of the rug, noting and photographing areas of minor damage and small areas of losses due to moth damage. One method used to combat moths and other insects is to freeze the textile for several days. This rug has been through the freezing process. Making record of the condition of the rug as it exists today allows confirmation of any changes during future inspections. Visible in the image at the right is a small area of damage within the blue stripe where the warp threads have broken, or sprung, leaving the weft yarns loose. When we had finished our notations about the artist, medium, condition, etc, we carefully rolled the rug, keeping it wrinkle-free, and carried it back to its storage home.

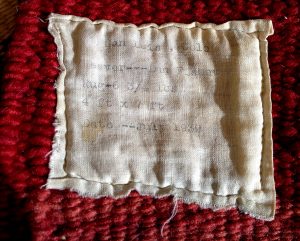

Cloth label with inscription, sewn to the back of the rug

This is one of the few Rio Grande textiles in the Luther Bean collection for which we have information on the weaver. (Unknown weavers are typical of Rio Grande textiles in museum collections.) An inscription in faded type on the cloth label sewn onto the back of the piece includes: San Luis, Colo. / Dan Fisher / Rug / July 1939.

Detail of the dye colors and ticking pattern in the stripes at each end of the rug

Later research uncovered the fact that Dan Fisher learned to weave during the Works Progress Administration project to revive the weaving craft held from 1935 to 1940 in San Luis, CO. He may have produced this rug as part of his work in the weaving classes. Fisher identified this piece as a rug. Visual inspection confirmed this use, as the yarns on the top surface of the rug are well flattened but the yarns on the underside of the rug are still quite plump.