History Colorado Center, Denver, CO

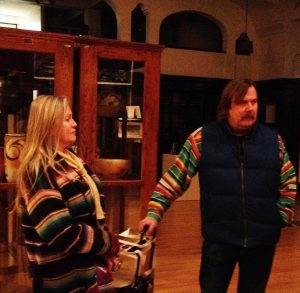

History Colorado Center in Denver, Colorado is home to the Woodard Collection of Rio Grande textiles. From the same family, the Luther Bean Museum received the Woodard Collection of southwest pottery, retablos (Hispanic sacred paintings on wood), and antiques. Part of the internship was to visit museums with collections similar to ours and to learn how they manage various aspects of their collections. I contacted History Colorado and met with Bethany Williams, Collections Manager. In advance of our meeting, she sent me a document listing the Woodard Collection textiles with photographs, so that I could choose several to view during my visit.

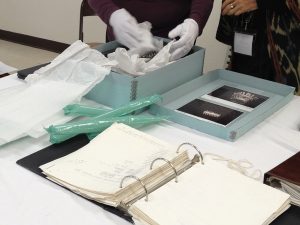

We started in the cavernous room that houses a large portion of their textile collections. Climate is controlled at 70 degrees F with 40% humidity. Rows of huge rolling racks hold the textiles on separate rods. The textiles are rolled around an archival tube with archival tissue paper to avoid dye transfer from one part of a textile to another. The rolled textile is then wrapped in a layer of plastic and the ends of the plastic are secured with cotton twill tape.

In another large room, I viewed three Rio Grande textiles from the Woodard Collection. The tag attached to the textile has extensive identifying information in addition to the accession number. It includes a photograph, a description of the object with colors, the object dimensions, the donor and date, and instructions on how to store the object.

For pest management, they use sticky traps deployed at entrances, corners, and at intervals, and regular spraying for ants and spiders. When needed, live traps are used for mice. If evidence of moths or carpet beetles is found, they freeze the textiles and then vacuum both sides using a Nilfisk vacuum with adjustable suction and a screen at the nozzle.

History Colorado displays textiles using a cotton muslin sleeve through which may be inserted a metal rod or magnets. They are moving to using slant boards at a 30-degree angle to help support and to avoid the stress of gravity on the textiles. Their slant boards are fabricated of low-VOC MDF wood with a layer of Mylar between the MDF and the textile. We also reviewed collections documentation and management on the Argus database system, which enables public access to search their collections.