Steps to Build Confidence in Athletes: A Guide for Coaches

By: Riley Robbins

Vince Lombardi once said, “Confidence is contagious.” He also said, “So is lack of confidence.” Herein lies the conundrum that faces coaches across the world. Why is confidence so important in sport? High levels of confidence have been shown to decrease concentration disruption while improving concentration ability as well as improve resiliency and reduce anxiety. In other words, having confidence increases focus and the ability to hold it. It is plain to see why confidence is desirable for an athlete to possess. Every coach wants their athletes to be confident so that they will have the best chance at success, but that implies that an athlete with no confidence will likely not experience success. We find ourselves in a chicken vs. egg conundrum following this type of logic. Basically, the prevailing mindset in sport is that confidence breeds success. But, as I’m sure we all remember from our introductory psych class, Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy suggests that self-efficacy (confidence) is built when someone experiences success in a certain endeavor. So, does confidence breed success, or does success breed confidence?

There is a clear answer as to which direction of causality is correct here. Just as researchers discovered that the chicken did, in fact, come before the egg, we know that success must come before confidence. Okay, great. But how?

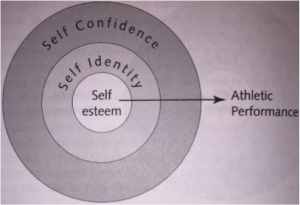

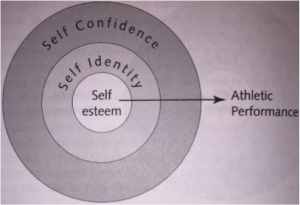

Build confidence from the inside → out. Ralph Vernacchia’s “Inside Out” approach to confidence building (see figure) does a great job of demonstrating the link between self-esteem, self-identity, and confidence as they relate to athletic performance.  This diagram illustrates how one’s self-esteem and self-identity are the foundation of self-confidence which, in turn, affects athletic performance. Now, picture the arrow in the above diagram pointing the opposite direction, resulting in an outside-in approach. This type of approach causes an athlete’s confidence and self-esteem to be dependent upon success in sport (i.e. winning). Anyone involved in sport knows that winning cannot and will not persist forever. An outside-in approach can provide an athlete with confidence, but it is neither sustainable, nor desirable.Because self-worth hinges upon success in this scenario, an athlete may go to extremes and participate in ultimately self-destructive behavior to achieve success – including cheating or even using performance enhancing substances. Athletes in this scenario may find themselves loathing the idea of competition and possibly even trying anything new, due to a deep fear of failure. An outside-in approach is cultivated through coaching and parenting methods that are based on using fear and guilt as motivators, and sadly, this is far too common in sport culture. Obviously, the inside-out approach is superior for developing robust and sustainable confidence, but how do we coach with an inside-out approach?

This diagram illustrates how one’s self-esteem and self-identity are the foundation of self-confidence which, in turn, affects athletic performance. Now, picture the arrow in the above diagram pointing the opposite direction, resulting in an outside-in approach. This type of approach causes an athlete’s confidence and self-esteem to be dependent upon success in sport (i.e. winning). Anyone involved in sport knows that winning cannot and will not persist forever. An outside-in approach can provide an athlete with confidence, but it is neither sustainable, nor desirable.Because self-worth hinges upon success in this scenario, an athlete may go to extremes and participate in ultimately self-destructive behavior to achieve success – including cheating or even using performance enhancing substances. Athletes in this scenario may find themselves loathing the idea of competition and possibly even trying anything new, due to a deep fear of failure. An outside-in approach is cultivated through coaching and parenting methods that are based on using fear and guilt as motivators, and sadly, this is far too common in sport culture. Obviously, the inside-out approach is superior for developing robust and sustainable confidence, but how do we coach with an inside-out approach?

- Build strong relationships with your athletes. An inside-out approach is grounded in social support. According to successful collegiate coaches, social support is key to building mental toughness – of which self-confidence is a major part of. Strong relationships can be cultivated by creating a supportive culture emphasizing personal improvement for athletes. Coaches can build a strong relationship with athletes and cultivate an improvement-oriented culture by making it a habit to provide positive constructive feedback regardless of the outcome of their athletes’ performance. Eventually, your athletes will understand that you care for them and about their development whether they win, lose, or draw. This allows your athletes self-esteem to grow uninhibited. Your athletes will begin to develop a strong sense of identity centered around self-improvement – what we refer to in the sport psychology world as “mastery orientation.” As your athletes begin to center themselves around improving, desiring improvement will become a trait. It will infiltrate everything they do, and they will have more confidence to try new things.

Building a strong relationship gives you credibility with your athletes, which allows you to teach them mental strategies that can increase their confidence. For example, teaching your athletes to practice positive motivational self-talk can help control anxiety, thus improving confidence and subsequently, performance. Your relationships with your athletes will help you discern who is susceptible to negative self-talk or negative thoughts that damage self-confidence. Examples of these should be apparent – you may hear things like “I suck”, or, “I can’t do this.” However, these negative expressions may be less obvious. Be on the lookout for athletes who constantly blame uncontrollable factors for their performance. This athlete may be subject to an outside-in influence outside of sport. Teach your athletes to recognize that negative thoughts are natural, but to dismiss them and replace them with a positive thought instead. A thought that is motivational in nature may work best in sport, but anything positive will do if you allow your athletes to personalize it for themselves. Teaching your athletes to replace negative thoughts with positive ones is rooted in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a widely recognized treatment used by clinicians in which the main goal is to reduce anxiety by slowly changing the way a person views a situation.

The strong relationship you create with your athletes combined with your athletes’ high self-esteem and desire to improve will allow you to hold them to a higher standard of performance. Strong relationships with your athletes permit you to demand success from them. I know what you’re thinking, “I thought you said perpetual winning was not possible?” You would be right, but that assumes success should be defined as how much you win.

- Redefine success. If I asked 100 coaches how they defined success, I would expect to hear definitions that are centered around winning from most of them. This sort of thinking paradoxically sets you and your team up for failure. Statistically speaking, more seasons end in defeat than victory. Change your definition of success to include high effort, focus, proper technique, and self-improvement. This allows you to be demanding of your athletes while still setting them up for success because, in this context, success is not based on performance outcomes. The advantage to measuring success as completion of tasks based on effort, focus, and technique, is that these things are controllable for your athletes. Controllable sources from which athletes can derive confidence are superior to uncontrollable sources such as performance. To simplify, an athlete can control the amount of effort and hustle they give and their focus upon executing a game plan with proper technique. They cannot control how their opponent performs in a game, or even how their teammate performs in a practice. This is not to say that success should not be measured by performance, but that success should be simply measured in relation to one’s previous performance, not how their performance stacks up against others’. Success should be measured by individual improvement.

If you commit to redefining success, you must logically redefine failure. As a coach, you should only view a performance as a failure if your athletes do not give full effort and are not fully focused. A failure should be an introspective teaching moment for you to use.You should embrace failure as natural, and learn to use it to motivate your athletes to give their best effort and focus the next time. Further, teach your athletes that they should embrace failure as natural, and key to improving. This is crucial to instilling resiliency. You should not blame your athletes for a failure. Instead, use your strong relationship with them to find out why they did not give their best effort or why they were not focused. There may be reasons for this beyond sport (if you have a strong relationship with them, you may find out that they have troubles outside of sport that are affecting their ability to be successful in sport). Be supportive. It is your job to use failures as an emotional reference point to teach your athletes to appreciate success that much more.

- Set athletes up to succeed, then celebrate success. Use practices as the primary domain for building confidence. Set up drills and tasks that are challenging, but can be achieved by using effort, focus and proper technique. It does not matter what drills or tasks you decide to employ, but here are some guidelines: choose drills that do not involve your athletes standing around much, change the drills frequently to avoid monotony, and always acknowledge high effort. Keeping your athletes engaged by avoiding drills that involve standing around is a way to train high levels of focus. Changing drills to avoid monotony encourages a consistently high level of effort. As a bonus, if your athletes are constantly giving high effort, you will likely have to employ less conditioning as part of practice, which your athletes will appreciate.

A common mistake among coaches comes in the form of criticizing their athletes when they make mistakes. Instead, if your athletes’ performance comes up short due to lack of effort or focus, communicate to your athlete that effort and focus are the most important things you want them to achieve, not a “winning” outcome. Then, use constructive positive feedback to help them get it right the next time. Athletes will certainly struggle achieving some tasks, but do not give up as a coach. Giving up as a coach demonstrates that it is okay to surrender as an athlete and beyond. Instead, be persistent. Finally, when an athlete masters a certain task, celebrate it together. This not only solidifies your relationship, but it teaches resiliency, persistence, and instills confidence because they achieved success. Relay to your athletes that they are loved and appreciated regardless of the outcome of their performance.

If you follow these three steps, your athletes will experience success and ultimately confidence. Building confidence in athletes is important for you to accomplish as a coach for reasons other than simply improving their sport performance. Depending on the context, you may be coaching athletes who struggle in school. Building confidence in sport allows these youths to take positive risks in school they wouldn’t have taken without it. Because they have strong sport confidence, they have a sort of safety net that they can fall back on should they struggle, and it links back to their strong self-esteem and improvement-oriented self-identity you have helped them build through sport. In other words, their confidence helps remove fear from their decision-making processes.

Conceptually, building confidence in your athletes should be easy. All you must do is build relationships with your athletes, define success as how much effort, focus, and attention to technique your athletes display, and help them celebrate their success. As they celebrate their success, their confidence will continually root itself into their personality. It is your job to maintain this confidence by repeating the steps outlined above. A perk of having a team full of athletes who possess high self-esteem and self-confidence, is that this type of athlete is more likely to set aside their personal goals in favor of giving effort and focus towards team goals. Having many of this type of athlete on your team is one of the first steps towards winning a championship. Not that that matters, anyway.

Riley Robbins

MS Applied Sport Psychology Student

robbinsrt@grizzlies.adams.edu

Concentration (attentional focus) has grown vastly in literature and research involving sports and has been shown to become even more important for athletes in a developmental stage. Concentration as the ability to direct your individual attention on cues in the environment that are relevant to the task at hand. For example, the field goal kicker on the left may be focusing his attention on a focal point in between the uprights, the ball or even on his own mechanics without specifically thinking about where he is looking. Hopefully this kicker isn’t focused on the defensive players trying to block the ball or a random person in the crowd. Understanding the difference between directing your attention externally and internally focus for concentration, is extremely important for coaches teaching any new skill. Paying attention to external cues has shown to be the most effective with any fine motor skill tasks like throwing a ball, kicking a ball, swinging a bat, jumping, back pedaling, etc. Below is a model (http://www.science.smith.edu/exer_sci/ESS565/MPres1/sld011.htm) created to show the difference between broad-narrow and external-internal attention.

Concentration (attentional focus) has grown vastly in literature and research involving sports and has been shown to become even more important for athletes in a developmental stage. Concentration as the ability to direct your individual attention on cues in the environment that are relevant to the task at hand. For example, the field goal kicker on the left may be focusing his attention on a focal point in between the uprights, the ball or even on his own mechanics without specifically thinking about where he is looking. Hopefully this kicker isn’t focused on the defensive players trying to block the ball or a random person in the crowd. Understanding the difference between directing your attention externally and internally focus for concentration, is extremely important for coaches teaching any new skill. Paying attention to external cues has shown to be the most effective with any fine motor skill tasks like throwing a ball, kicking a ball, swinging a bat, jumping, back pedaling, etc. Below is a model (http://www.science.smith.edu/exer_sci/ESS565/MPres1/sld011.htm) created to show the difference between broad-narrow and external-internal attention.

Adams State University professor Lukus Klawitter balances extensive triathlon training while teaching multiple undergraduate and graduate level classes. Klawitter has a running background that started back when he was a young kid being raised in Hutchinson, Minnesota. Klawitter followed his brother’s footsteps by joining the cross country team in middle school. While running track and cross country throughout school, Klawitter also played hockey which Minnesota has a rich tradition with. He worked with a local bike shop in high school and found his passion for bicycles then. After high school Klawitter attended Moorhead State University in northwest Minnesota to compete in cross-country and track and field at the NCAA Division II level. While loving the sport and training hard, persistent injuries ended his collegiate running career after his freshman year. These injuries were the start of a four and a half year hiatus from full training. Klawitter finished his education at Moorhead in 2013 and then moved to Alamosa to pursue a master’s degree in exercise science. While continuing through the program he continued to cycle and swim and he then discovered his passion for mountain biking in the San Luis valley of Colorado. Klawitter began to fall back into full time training as he began to run more often.

Adams State University professor Lukus Klawitter balances extensive triathlon training while teaching multiple undergraduate and graduate level classes. Klawitter has a running background that started back when he was a young kid being raised in Hutchinson, Minnesota. Klawitter followed his brother’s footsteps by joining the cross country team in middle school. While running track and cross country throughout school, Klawitter also played hockey which Minnesota has a rich tradition with. He worked with a local bike shop in high school and found his passion for bicycles then. After high school Klawitter attended Moorhead State University in northwest Minnesota to compete in cross-country and track and field at the NCAA Division II level. While loving the sport and training hard, persistent injuries ended his collegiate running career after his freshman year. These injuries were the start of a four and a half year hiatus from full training. Klawitter finished his education at Moorhead in 2013 and then moved to Alamosa to pursue a master’s degree in exercise science. While continuing through the program he continued to cycle and swim and he then discovered his passion for mountain biking in the San Luis valley of Colorado. Klawitter began to fall back into full time training as he began to run more often.